Don Brown

Click logo to return to 'links-page'

Click logo to return to 'links-page'

Dear Aubrey

I fully support efforts to make contraction and convergence (C&C) the central framework for allocating national greenhouse gas emissions in the years ahead. C&C is also flexible enough to deal with several equity issues raised by others.

I [also] believe the new CBAT model should be of great value both to international climate negotiators, governments and NGOs engaged in international climate negotiations. It allows those interested in developing a global solution to visualize the otherwise complex interactions of international carbon budgets, atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, and emissions reductions commitments. Although I am personally familiar with the relationships between the variables represented in the CBAT, I found having the ability to change inputs to the model through the use of the CBAT made me understand at a deeper level the policy choices facing the international community. The CBAT model should be very useful for all who hope to understand future climate change policy options and the scale of the global challenge facing the world.

I have been engaged in climate change policy options since the 1992 Earth Summit at which the United Nations Framework Convention was opened for signature and have attended most of the Conference of Parties under the UNFCCC since then. Yet even though I have significant experience and knowledge about future climate change policy challenges, the CBAT model helped me visualize the significance of certain policy options facing the world.

Donald A. Brown

Scholar In Residence, Sustainability Ethics and Law, Widener University School of Law

Donald A. Brown

Scholar In Residence,

Sustainability Ethics and Law, Widener University School of Law, Pennsylvania, USA:

"I believe the new CBAT model should be of great value both to international climate negotiators, governments and NGOs engaged in international climate negotiations.

It allows those interested in developing a global solution to visualize the otherwise complex interactions of international carbon budgets, atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, and emissions reductions commitments.

Although I am personally familiar with the relationships between the variables represented in the CBAT, I found having the ability to change inputs to the model through the use of the CBAT made me understand at a deeper level the policy choices facing the international community.

The CBAT model should be very useful for all who hope to understand future climate change policy options and the scale of the global challenge facing the world. I have been engaged in climate change policy options since the 1992 Earth Summit at which the United Nations Framework Convention was opened for signature and have attended most of the Conference of Parties under the UNFCCC since then.

Yet even though I have significant experience and knowledge about future climate change policy challenges, the CBAT model helped me visualize the significance of certain policy options facing the world.

I also fully support efforts to make contraction and convergence (C&C) the central framework for allocating national greenhouse gas emissions in the years ahead. C&C is also flexible enough to deal with several equity issues raised by others."

The first public of the chart below was in the article above by Don Brown.

It was subsequently used by Sir David King at the IEA in 2016.

Sadly global CO2 emissions have only risen since 2010 (including in the USA).

Climate Change Ethics - Don Brown

In addition to these principles, over the last decade, several new emissions reductions frameworks have evolved, which have received widespread attention in the international community, particularly among non-government organizations participating in international climate change negotiations. These include allocation formulas called, "Contraction and Convergence" (C&C) and the "Greenhouse Development Rights" (GDR) framework.

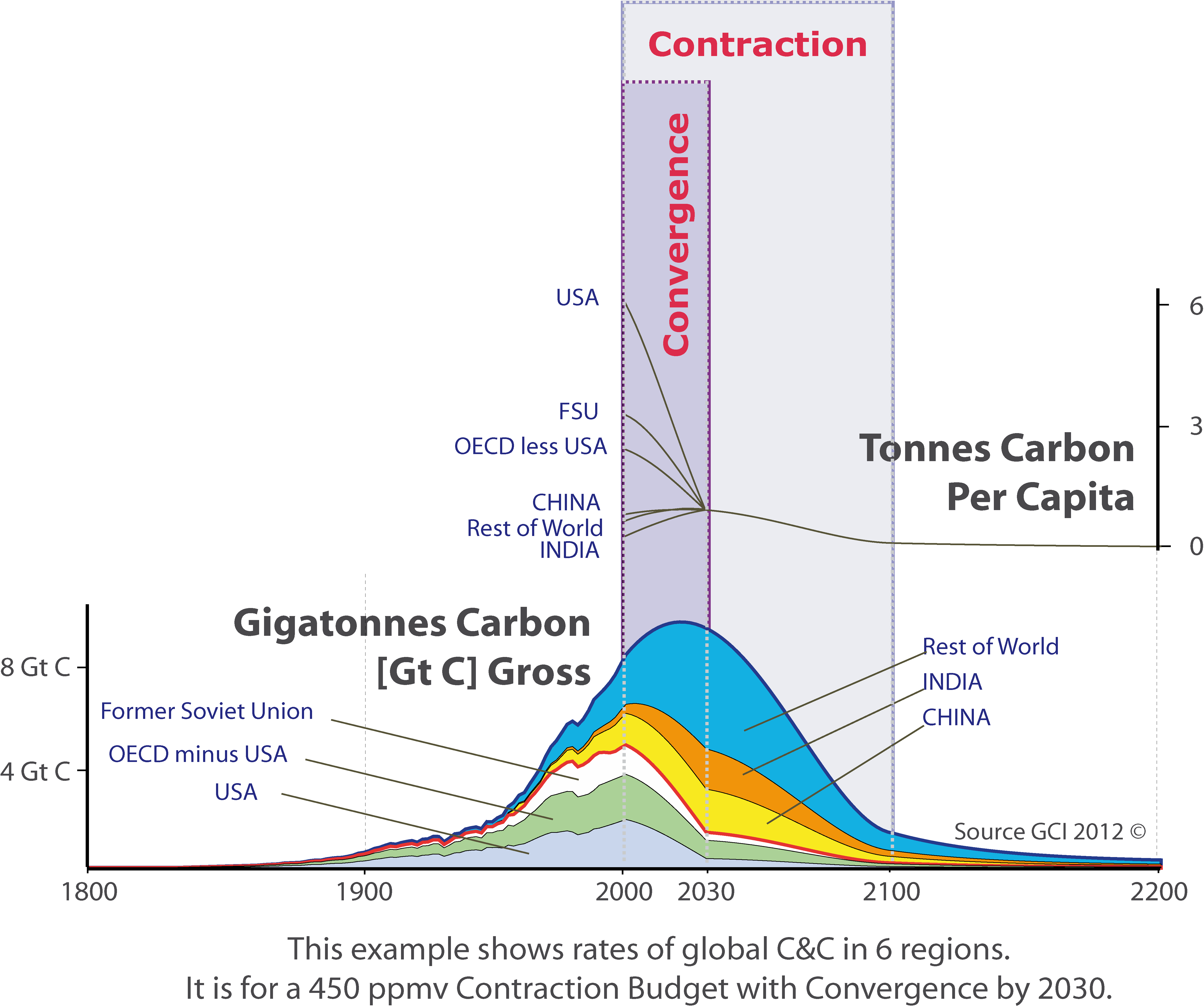

C&C was first proposed in 1990 by the London-based non-governmental Global Commons Institute (GCI 2010) (see Figure 6.3).

Basically, C&C is not a prescription per se, but rather a way of demonstrating how a global prescription could be negotiated and organized in a way that ultimately levels off on the basis of equal per capita emissions (Meyer 2000) .

Implementing C&C requires two steps. As a first step, countries must agree on a long-term global stabilization level for atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations as discussed in the last chapter. Once this is done a global greenhouse gas emissions budget can be calculated that would determine how many tonnes of greenhouse gases can be released into the atmosphere that will allow atmospheric concentrations to be stabilized. As a second step, countries need to negotiate a convergence date. That is, a date at which time the emissions allocated to each country should converge on equal per capita entitlements. During the transition period, a yearly global carbon budget is devised, which contracts gradually over time as the per capita entitlements of developed countries decrease while those of most developing countries increase. C&C would allow nations to achieve their per capita-based targets through trading from countries having excess allotments. And so, under C&C, nations eventually receive binding emissions reductions allocations that are distributed on the basis of equal per capita emissions for all humans.

How to calculate greenhouse gas allocations between nations has always raised tensions between the developed and developing countries; the latter arguing that they have a right and need for economic development to help poor people rise above grinding poverty. In fact, international climate negotiation has been plagued by global North versus South conflicts. Poor developing nations have been deeply worried that climate change policies will exacerbate existing injustices between rich and poor nations if the poor countries' ability to develop economically is thwarted by limits on greenhouse gas emissions.

The second allocation formula based upon equitable considerations is the GDR framework; a framework specifically designed to assure that poor people are not unfairly constrained in a world in which the global economy is constrained by limits on carbon (Baer et al. 2008). GDR begins with an ambitious emissions reduction pathway which, geared to the latest alarming evidence, has a relatively high probability of holding global warming below 2°C (Baer et al. 2008). GDR specifies that individuals whose income is below $7,500 are given the right to development. Under GDR these, by definition, poor individuals are not expected to help to pay the costs of the climate transition. Yet, individuals with incomes above the development threshold- by stipulation of GDR, the global consuming class- are thought of as having realized their right to development (Baer et al. 2008). Because of this, under GDR, they must shoulder the responsibility of curbing global carbon and the costs of adaptation from unavoidable climate change and compensation for climate damages (Baer et al. 2008).

Although some governments and organizations have endorsed either C&C or GDR, these frameworks have not yet been seriously considered by governments as the basis for setting emissions reductions commitments during recent climate change negotiations despite high levels of interest in these two approaches among non-government organizations. In fact, most nations have continued to avoid linking their commitments to greenhouse gas emissions reduction to levels that take equity into account.

Contraction and Convergence

An equal per capita allocation, the ultimate goal of C&C, would be consistent with principles of justice because: (a) it treats all individuals as equals and, therefore, is consistent with theories of distributive justice, (b) it would implement the ethical maxim that all people should have equal rights to use global commons, (c) it would not be inconsistent with the widely accepted polluterpays principle, except perhaps with historical emissions, and (d) it could recognize the need of developing countries to increase their emissions to meet the basic needs of their citizens by negotiating when the convergence date would need to be achieved. Before allocating any carbon budget- a budget necessary to achieve a safe global atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases on the basis of equal per capita allocations- a case can be made that per capita emission levels should be adjusted to consider historical cumulative emissions. C&C has been criticized on the basis of its failure to deal effectively with historical emissions; a feature of C&C that could mean poor nations have insufficient levels of greenhouse gas emissions to allow them to use fossil fuels to economically grow out of poverty. Proponents of C&C have proposed some adjustments to C&C to deal with this limitation, including adjustments to the date of convergence and increased funding for adaptation to deal with this problem. And so as adjusted, C&C satisfies ethical scrutiny and can be seen as a way of operationalizing the meaning of equity under the UNFCCC.Greenhouse Development Rights

The GDR framework discussed above also satisfies the minimum ethical criteria for allocating targets for national greenhouse gas emissions in that differences between national targets are based upon ethically relevant criteria, including basic needs of poor nations for economic development, the economic capacity of rich countries to invest in greenhouse gas-friendly technologies, and historical emissions considerations. Yet GDR is vulnerable to the criticism that the criteria it follows for determining economic prosperity levels- and, therefore, emission reduction obligations (for example the proposed $7,500 economic prosperity level that exempts some below it from emissions reduction targets)- are so arbitrary as to raise questions of distributive justice. Others have criticized GDR on the basis of its attempts to solve not only climate change, but also inequitable economic development. In so doing, GDR conflates two problems in such a way that it makes political agreement very unlikely (Kraus 2009). More specifically, Kraus argues that:In order to make GDRs fully operational, nations need to agree upon a number of matters including the emergency emissions trajectory, the precise level of the development threshold, the year when responsibility starts, the formula to calculate the RCI, and the respective weights of capacity and responsibility .... This reduces the transparency of the GDRs concept and significantly increases the necessary amount of data. Compared to GDRs, C&C has a higher degree of institutional feasibility. Due to its simplicity, C&C only requires data about emissions and population numbers of all nations. (Kraus 2009)

Because of the increased complexity of negotiations that would be required to implement GDR, Kraus believes it is not politically feasible. Ethics would not support a formula that is almost impossible to implement. Of course, proponents of GDR deny that complexities of GDR create practical barriers to its adoption and implementation. And so GDR passes ethical scrutiny, although some practical problems need to be answered.

Reviews

Climate change raises some of the most profound ethical issues of our time. And yet, for thirty years our policy responses have evaded comprehensive ethical analysis. This book puts an end to this 'grave and unjust omission. However, the outstanding contribution of this book is its explanation of how ethical considerations can bring moral responsibility to the forefront of climate policy and action.

Prue Taylor, University of Auckland, New ZealandDon Brown navigates the troubled waters of climate change denial. He deconstructs the cynical efforts by vested interests to pollute the public discourse by means of a climate change disinformation campaign. Brown also makes a compelling argument that limiting carbon emissions and mitigating climate change is the ethical imperative of our time.

Michael Mann, Pennsylvania State University, USAIn this fascinating book, Donald A. Brown draws on his vast experience to explore one of the great ethical issues of our time, and provides recommendations about how to bring ethical issues into the formulation of global warming policy responses.

Richard Alley, Pennsylvania State University, USAClimate change is now the biggest challenge faced by humanity worldwide and ethics is the crucial missing component to the debate. The climate change threat is caused by the wealthiest of the world's population putting the most vulnerable at risk. The ethical dimension of climate change is therefore crucial, as the victims can only hope that those responsible for climate change will appreciate their obligation to the rest of the world and reduce their emissions accordingly. This book examines why a thirty-five-year discussion of human-induced warming has failed to acknowledge fundamental ethical concerns, and subjects climate change's most important policy questions to ethical analysis. Climate change is a global problem that requires a global solution, and given that many nations refuse participation due to perceived inequities of an international solution, this book explains why ensuring that nations, sub-national governments, organizations, businesses and individuals acknowledge and respond to their ethical obligations is both an ethical and practical mandate. The book examines the reasons why ethical principles have failed to gain traction in policy formation and recommends specific strategies to ensure that climate change policies are consistent with ethical principles. It is the first book of its kind to go beyond a mere account of relevant ethical questions to offer a pragmatic guide to how to make ethical principles relevant and integral to the world's response to climate change. Written by Donald A. Brown, a leading voice in the field, it should be of interest to policy makers, and those studying environmental policy, climate change policy, international relations, environmental ethics and philosophy.

Donald A. Brown is Scholar in Residence on Sustainability Ethics and Law at Widener University School of Law, USA.Contraction & Convergence and Greenhouse Development Rights:

A Critical Comparison Between Two Salient Climate-Ethical Concepts

Taken together, the above suggests that GDRs performs worse against all of the four criteria. In its present form, GDRs is also inappropriate to implement the right to development and to solve the development crisis. Compared to GDRs, C&C is easier to negotiate and to implement, C&C has a higher potential to lead to a global climate compromise, C&C rests on less contestable ethical foundations, and has a higher potential to stimulate changes in public attitudes and awareness. All in all, C&C is the preferable concept. However, with a view to tackling the climate challenge, C&C should put more emphasis on the fact that in the future for many countries the conventional development path based on increasing economic growth and the consumption of fossil fuels will no longer be feasible. Climate change largely challenges prevalent international institutional control mechanisms. To overcome the climate crisis, it is therefore the more important to create a global atmosphere of trust as a basis for comprehensive cooperation across social, economic, and cultural divides. The image of a divided world which is in the centre of the GDRs Framework (e.g. Baer et al. 2008:91) may aptly describe reality but it may not show a vision of how to bridge the gap between rich and poor, North and South. C&C, however, evokes the image of a global community in which, under growing pressure, people in poor and rich countries alike act together to bring about a more careful and sustainable management of the atmosphere. However, a global climate partnership based on C&C will only be achieved once the obligation of rich countries to assist adaptation in poorer countries is duly recognized. This is not a question of charity but a question of justice and fairness.

Climate Ethics Critical Analysis of Climate Science and Policy

Rock Ethics Institute, Pennsylvania State University

Because of the long phase-in time that would be required to move toward per capita allocations in the developed nations. those developing nations pushing for per capita allocation have proposed an approach usually re ferred to as 'contraction and convergence’. Contraction and convergence means an allocation that would allow the large emitter nations long enough time, perhaps thirty or forty years to contract their emissions through the replacement of greenhouse gas-emitting capital and infrastructure and eventually converge on a uniform per capita allocation.Support for contraction and convergence has been building around the world with the European Parliament in 1998 recently calling for its adoption with a 90 percent majority. A per capita allocation would be just for the following reasons:

- It treats all individuals as equals and therefore is consistent with theories of distributive justice

- It would implement the ethical maxim that all people should have equal rights to use a global commons.

- It would implement the widely accepted polluter-pays principle

American heat: ethical problems with the United States’ response to global warming

Donald A. Brown.

Since most nations entered the Copenhagen and Cancun negotiations as if national interest rather than global responsibility to others was an adequate basis for national climate change policies, the commitments made under the Copenhagen Accord and Cancun agreements fail to satisfy equity criteria. In fact, in the lead-up to Copenhagen, most of the justifications for national commitments that had been announced by countries to reduce their emissions were exclusively focused on whether they met global goals to reduce GHG emissions unadjusted by equity considerations.

There have been several proposals discussed by the international community about second commitment period frameworks that would expressly incorporate equity into future ghg emissions reductions pathways. Two such frameworks are known as “Contraction and Convergence” (C&C, 2009) and “Greenhouse Development Rights” (GDR) (Bear and Athanasiou, 2009) frameworks. In the lead-up to Copenhagen, all major GHG emitting nations ignored the C&C or GDR frameworks or any other comprehensive framework that took equity into account. In fact, the Copenhagen Accord and the Cancun agreements allowed each nation to identify its emissions reduction commitment based upon voluntary national considerations without regard to equity.

An Ethical Analysis of the Cancun Climate Negotiations Outcome

Donald A. Brown Associate Professor, Environmental Ethics, Science, and Law, Penn State University